Study smarter. Pass sooner. Live better

Evidence‑based exam prep for junior doctors - spaced repetition, active recall, timeboxing, and resilience strategies grounded in cognitive science.

Trusted by doctors preparing for FRACGP, Anesthesia, and Physician Training.

What you’ll get (at a glance)

- A personalised study plan mapped to your roster and exam date

- High‑yield techniques to increase recall and confidence

- Wellbeing micro‑habits to protect focus and energy

- Clear milestones so you always know what’s next - and what to stop

Why this approach works

Medical training demands precision and endurance. Your study should, too. We combine cognitive science and performance psychology so you can:

- Flatten the forgetting curve with spaced repetition

- Strengthen retrieval using active recall (not passive reading)

- Protect focus with timeboxing and short recovery windows

- Build exam confidence through communication and mindset techniques

“You wouldn’t use old technology on patients, so don’t use outdated study methods on yourself.”

Real results

“I studied exactly as advised - spaced repetition, active recall, sleep, family time - and passed each written exam on the second go, and then my clinical exam the first time.”

“I’m so relieved I now have a study plan.”

“Practising in this way is already enough to boost up my morale.”

Your plan in 3 Steps

- Book a 1:1 Zoom

50 minutes. Bring your roster and exam timeline. - Receive your personalized plan

Recall blocks, spacing intervals, and wellbeing routines—built around your shifts. - Train, track, adapt

Weekly checkpoints keep you focused. Swap cramming for deliberate practice.

Explore the study system

Use these focused guides to deepen specific skills

Study Smarter Not Longer

Use high value study techniques |

Wellbeing for SuccessSleep, recovery, and stress control |

Burnout and ResilienceSustainable performance under pressure |

Failure and Growth MindsetTurn setbacks into progress |

Time ManagementTimeboxing around shifts and clinics |

Adaptive Coping StrategiesCalm under exam conditions |

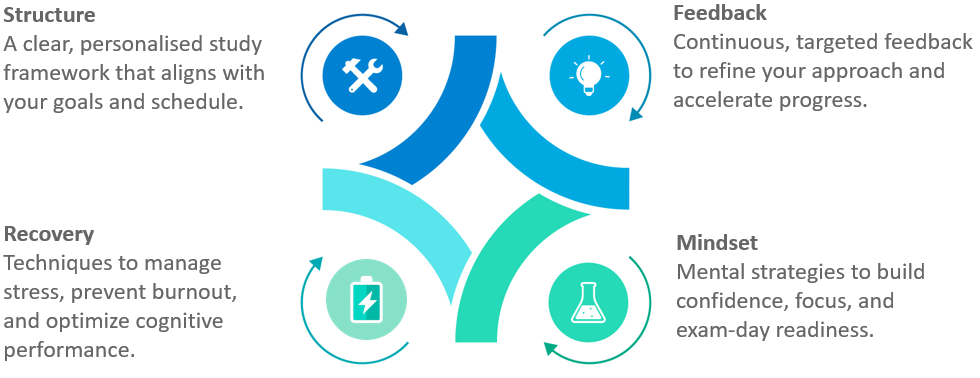

What Makes Us Different

Most study advice is anecdotal.

Ours is evidence-based.

We combine:

- Cognitive science

- Elite performance coaching

- Wellbeing and resilience training

- Real stories from doctors who’ve been there

Whether you’re sitting your Fellowship, primary, or clinical exams, we’ll help you build a study plan that works for your brain, your schedule, and your life.

We help you train your brain like a muscle—strong, flexible, and ready for the challenge ahead.

“The most successful candidates don’t just study harder—they train smarter. Like elite athletes, they follow a system that balances effort with recovery, strategy with feedback, and knowledge with mindset.”

Final Word

You’re not just preparing for an exam. You’re preparing for a career that demands clarity under pressure, compassion under fatigue, and excellence under scrutiny.

That kind of career deserves more than outdated advice and burnout-inducing study habits. It deserves a system that respects your time, protects your wellbeing, and empowers your performance. Because passing your exams isn’t just about what you know—it’s about how you prepare, how you recover, and how you show up when it matters most.

So don’t settle. Don’t sacrifice your health for hustle. Don’t study harder - study smarter.